Leaving a lasting impact on Environmental and National Park Preservation in the United States

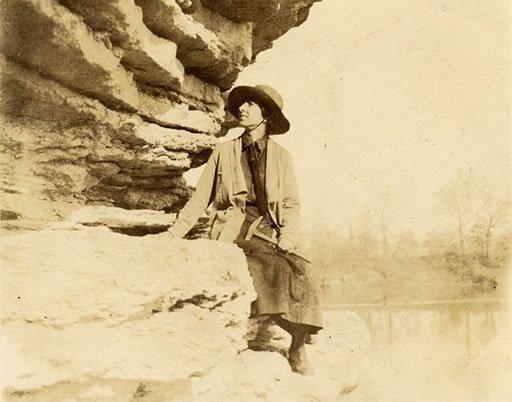

Isabel Bassett Wasson, a geologist, was one of the early female Rangers at Yellowstone National Park

Lower Yellowstone Falls as seen on our adventure tours

Our company mission focuses on travel in small groups, along the back roads of the Western USA, guiding visitors through the stunning scenery, natural wonders and adventure travel destinations that abound in this expansive country. All the experiences we offer are only possible thanks to the people who had the foresight to study and protect these wonderful places. In celebration of international Women’s month, her are a few of my favorite inspirational stories of women who worked to understand and preserve our beautiful landscapes and ecosystems- with courage, intelligence and a sense of adventure.

Celia M Hunter (1919 – 2001) – pilot, adventurer, conservationist

“You just have to keep a fire in your belly, and you just go for it, and when you do, you can make a tremendous difference.”

Celia Hunter’s love for adventure led her to the cause of environmental conservation. She learned to fly a variety of military aircraft with the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots during the second world war. Afterword, Hunter and her friend Ginny Wood, frustrated that as women they had not been able to fly to the staging grounds in Fairbanks with the military, decided to fly there on their own. They made a deal with a pilot in Seattle to fly two of his planes to Alaska. After a long and difficult journey, the two women found themselves stranded in Fairbanks due to a particularly brutal winter, and Hunter found a job with a travel agency where she planned sightseeing tours and served as a flight attended on new tourist flights.

After studying in Sweden and taking some time to bicycle around war torn Europe, Hunter returned to Alaska with Wood and Wood’s husband to start Camp Denali, a rustic vacation destination in a beautiful area. As early pioneers in ecotourism, Hunter and her friends built cabins from locally harvested trees and reclaimed material.

Captured by the beauty of this stunning region Hunter soon found herself involved in the fledgling conservation movement. She helped found the Alaska Conservation Society whose many efforts included working to stop a proposed nuclear blast that would create an artificial harbor and testifying in favor of the creation of the Arctic National Wildlife Range (ANWR). Hunter worked for conservation for the rest of her life.

She was offered a position on the Governing Council of the Wilderness Society and by 1976 she had become president of the organization, making her the first woman to head a national environmental organization. She was awarded the Sierra Club’s John Muir Award in 1991, and the Wilderness Society’s Robert Marshal award for her lifetime of conservation work.

On the night of her death at age 82, Hunter hadn’t stopped working for her cause. According to the Alaska Conservation Foundation she was found writing letters to congress advocating against drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

Hunter was also known to be a mentor to young women looking for adventure and service in the field of conservation. In her last radio interview, she said

“Change is possible, but you have to put your energy into it. You can’t expect me, I’m past 80, to be the mover and the shaker of this, but people like you are. And you’re going to have to bite the bullet and really decide what kind of world you want to live in.” Source Alaska Conservation Foundation.

Alice Eastwood, botanist

Alice Eastwood (1859 – 1953)- Self-taught botanist, curator of the San Francisco Academy of Sciences, mountaineer

Canadian Born Alice Eastwood moved with her family to Colorado at the age of 14, in 1879. Although Alice had a somewhat difficult childhood, as her father’s ailing business ventures necessitated her to work as well as take care of her younger sister, she remained an eager student. She reportedly always had an interest in plants and gardening, and it was the gift from a high school teacher of botany manuals that started her earnest education in botany.

Upon graduating at the top of her high school class, Eastwood couldn’t afford to go to college, so she took a job teaching at her high school and pursued her interest in botany in her spare time, reading manuals and hiking in the Rocky Mountains to collect and study samples. Self-taught, Eastwood was so successful and knowledgeable that she was asked to guide famous British biologist Alfred Russel Wallace up Grays Peak, one of the Colorado Rockies high peaks. That she was sought out by this famous naturalist, who worked closely with Charles Darwin, was certainly impressive, and so was hiking the 14,000 ft peak in the skirt required of women during this era.

After a clever real estate investment in growing Denver allowed her enough money to leave her teaching job and travel west to visit California, she quickly made friends and was offered a position the herbarium of the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. She traveled extensively into remote areas on horseback and foot on her own and with other researchers, collecting samples for the Academy and her own research.

Eastwood got along well with her colleagues and her sense of adventure was not limited by the gender expectations of her time. Years later when she was collecting samples in Northern California she was invited by some men to hike to the peak of Mount Shasta, a snowy volcanic peak that towers above other mountains in the region. Eastwood accepted, and later wrote about sledding down from the peak on her skirt.

She was living in San Francisco when the famous earthquake of 1906 hit, devastating the city and shaking the coast from Eureka to the Salinas Valley. The earthquake caused massive fires which multiplied the destruction all over the city, including the Academy of Sciences building to which Eastman rushed as soon as the quaking had stopped. When she arrived, she found that the building was severely damaged and threatened by a nearby fire. Concerned for some of the most important specimens located on the 6th floor of the building, Eastwood and a friend made their way into the building only to find the staircase destroyed. Undaunted, Eastwood reportedly climbed freehand to the 6th floor and lowered the most precious samples down to the ground before they had to leave due to the encroaching fire. (I first heard about Alice Eastwood from an interpretive range in Sequoia National Park, she said that Alice Eastwood climbed a mastodon skeleton to reach the the type collection, but I have not been able to confirm this.)

Eastwood’s home was also lost in the aftermath of the quake, and she took the opportunity to leave the country and visit herbariums in England, later traveling to Alaska and Canada, helping to rebuild the Academy’s collection.

Although she is mostly known for her great scientific contributions to our knowledge and understanding of botany of the Western US, she was also directly involved in conservation efforts, stopping development on Mount Tamalpais and helping found the Save The Redwoods League.

I could go on about this incredible woman’s contributions and adventures: the many plants named for her, the fact that she continued to research and collect samples even after she was hit by a car at age 72, and even her botany lessons to John McLaren, creator of Golden Gate Park.

A woman deservedly recognized in her time, she traveled to Sweden at age 91 to be honored at the International Botanical Congress. Although she had many friends, Alice Eastwood made this long journey by herself, in keeping with her independent spirit.

A small group enjoys a redwood tree, Alice Eastwood helped start a campaign to protect theses ancient giants

Mollie Beattie (1947 – 1996) Forester, first female Director of US Department of Fish and Wildlife

“What a country chooses to save is what a country chooses to say about itself.”

– Mollie Beattie

First woman appointed director of Fish and Wildlife, worked on endangered species and clean water acts, over saw the re-introduction of wolves into Yellowstone

Beatie earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy and spent a few years in journalism before a trip with the Outward Bound outdoor education program changed the course of her life. Forgoing an offer to be a news person for a Vermont television agency, she enrolled in UVM’s new forestry program.

Beatie was one of the few female foresters of Vermont at the time when she asked to apply for the position of commissioner of forest parks and recreation for the state. (According to the news magazine Christian Science Monitor she bought a dress when she realized she was being considered for the position as she didn’t own one, and this commissioner position would require more formal office wear than her usual boots and jeans.)

As Director of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Beatie was responsible for enforcing the Endangered Species Act and protecting wetlands, while overseeing 7,000 employees. Although her tenure was brief due to illness, she accomplished a lot, despite a shrinking budget she expanded the refuge system adding 15 wildlife refuges and establishing many habitat conservation plans, as well as working to bring gray wolves back to Yellowstone National Park. Beatie took a holistic approach to wildlife preservation, working to protect species by managing the entire ecosystems.

After her death, President Bill Clinton signed legislation naming a section of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge after Mollie Beatie. According to the Washington Post, then Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt said

“[The Mollie Beattie Wilderness] symbolizes Mollie’s spirit: wilder, more powerful and more free from the influence of man than anywhere else in America.”

These women were clearly dauntless, striking out into new territory, and devoting their lives to the US’ wild places. They were also known for being teachers and mentors, eager to share their knowledge and encourage other women.

Today, in the spirit of adventure travel, I focused on a few women who had exciting stories. From science to education to policy woman have played a key role in environmental consciousness, land preservation and wildlife protection. Rosalie Barrow Edge, a suffragist and bird watcher, helped reshape the Audubon Society to protect birds and other species. Biologist Rachel Carson, author of Silent Spring is credited with spurring the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. Civil rights Activist Marjory Stoneman Douglas ignited American’s appreciation for the everglades with her influential book, River of Grass. Former First Lady “Lady Bird” Johnson’s beautification efforts called attention to habitat and species loss. These women and many others dedicated their lives to the study and preservation of the natural wealth of the United States, leaving their mark on the very National Parks, Monuments, and wilderness areas that we visit on our small group adventure tours.

Sources and Further Reading:

Alaska Conservation foundation

https://alaskaconservation.org/foundation/history-founders/celia-hunter/

“The Legacy of Ginny Wood and Celia Hunter” Denali Dispatch, (Camp Denali’s blog)

http://campdenali.com/blog/133576

Clinton, William J “Statement on Signing the Mollie Beattie Wilderness Area Act”, July 29, 1996, available via American Presidency Project

http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=53132

Dicke, William “Mollie Beattie, 49; Headed Wildlife Service” The New York Times, June 29, 1996

https://www.nytimes.com/1996/06/29/us/mollie-beattie-49-headed-wildlife-service.html

Estrada, Louie “MOLLIE BEATTIE DIES AT 49” The Washington Post, June 29, 1996

Fago, D’ann Calhoun “Mollie Beattie brakes for trees. Vermont’s first female forest commissioner talks about her work” The Christian Science Monitor, January 5, 1988

https://www.csmonitor.com/1988/0105/hmoll.html

Hart, John “Mount Tam’s First Botanist: Alice Eastwood and the Plants of Tamalpais” Bay Nature Magazine, September 25, 2017

https://baynature.org/article/tam-tams-first-botanist/

Ross, Michael “Flower Watching with Alice Eastwood” Naturalist’s Apprentice Biographies Carolrhoda Books 1997

Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_Eastwood

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celia_M._Hunter

Wilderness.org

https://wilderness.org/bios/former-council-members/celia-hunter